LANDSCAPE, OMNISCAPE, AND CONTEMPORARY ART

“Strangeness is the condition of the landscape.”

Lyotard, 1988

Landscape is everywhere. It defines our particular idea of nature, but it is not nature in its simple definition. We can think of a landscape as “a social product, the result of a collective transformation of nature, and the cultural projection of a society in a given space.”1

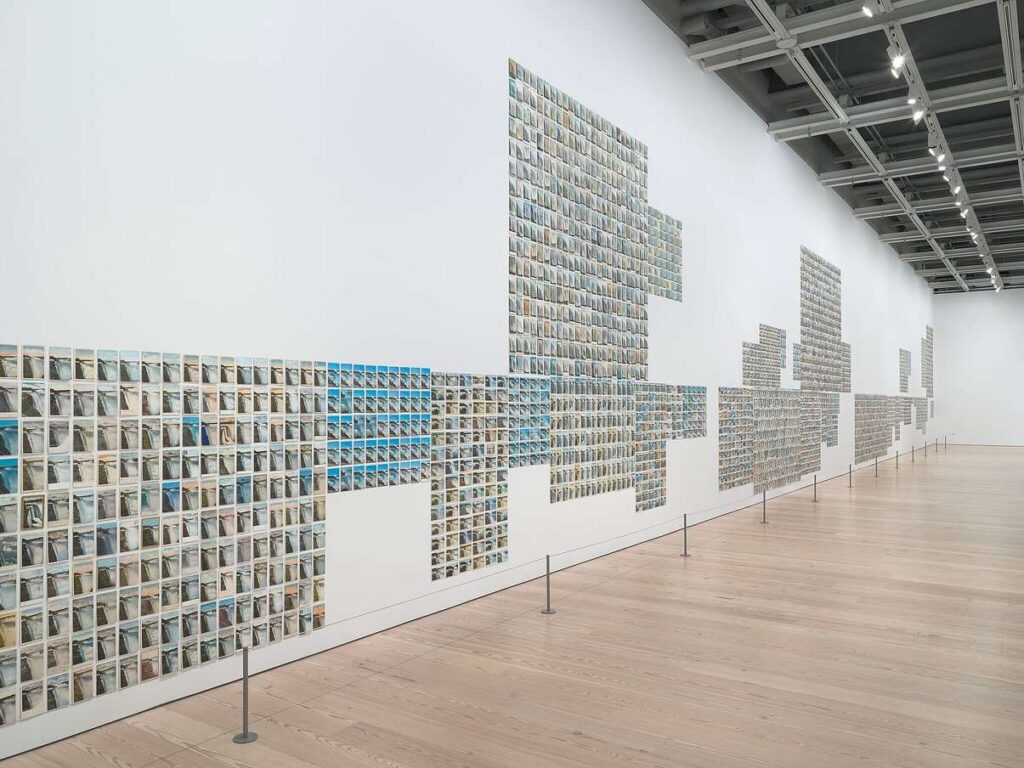

Zoe Leonard

You See I Am Here After All, 2008

The installation includes 3,851 vintage postcards

12’ x 147’

Everything that landscape encompasses as a cultural product and projection has consolidated its representation since the beginning. Landscape emerges the moment it is observed and expressed by someone, manifesting itself in its omnipresence, always inwards of the humanity in which it is immersed, but which externalizes it through the creation of images or in artistic production, in which it has been a recurring theme throughout history.

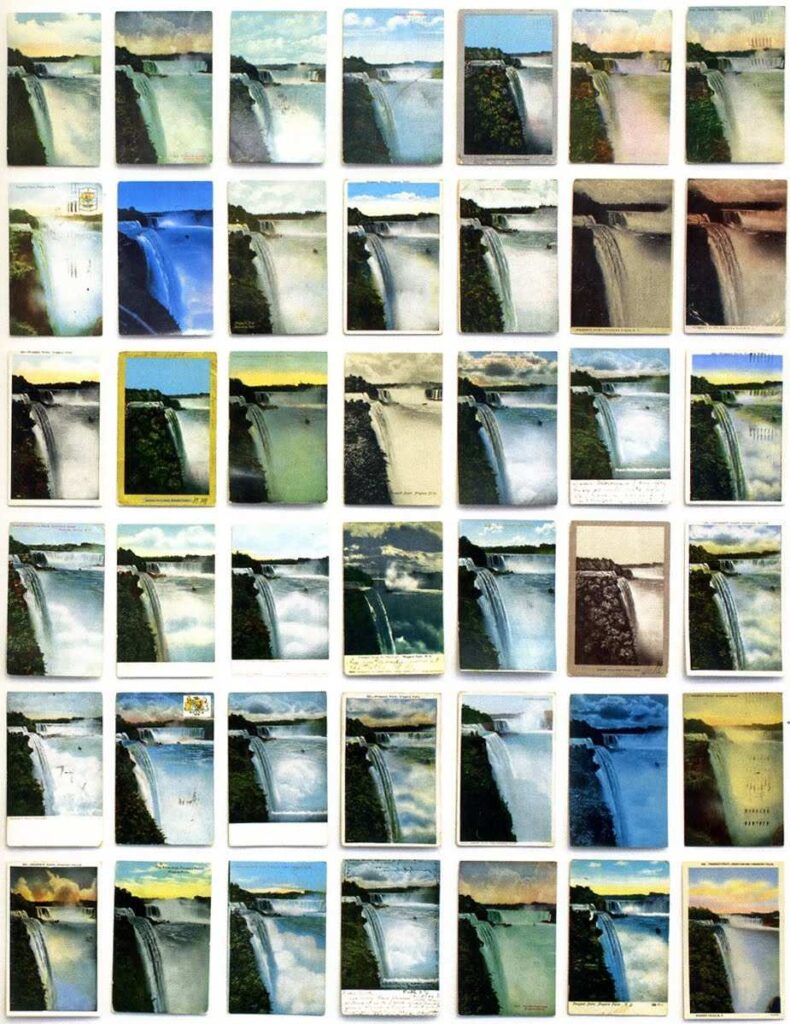

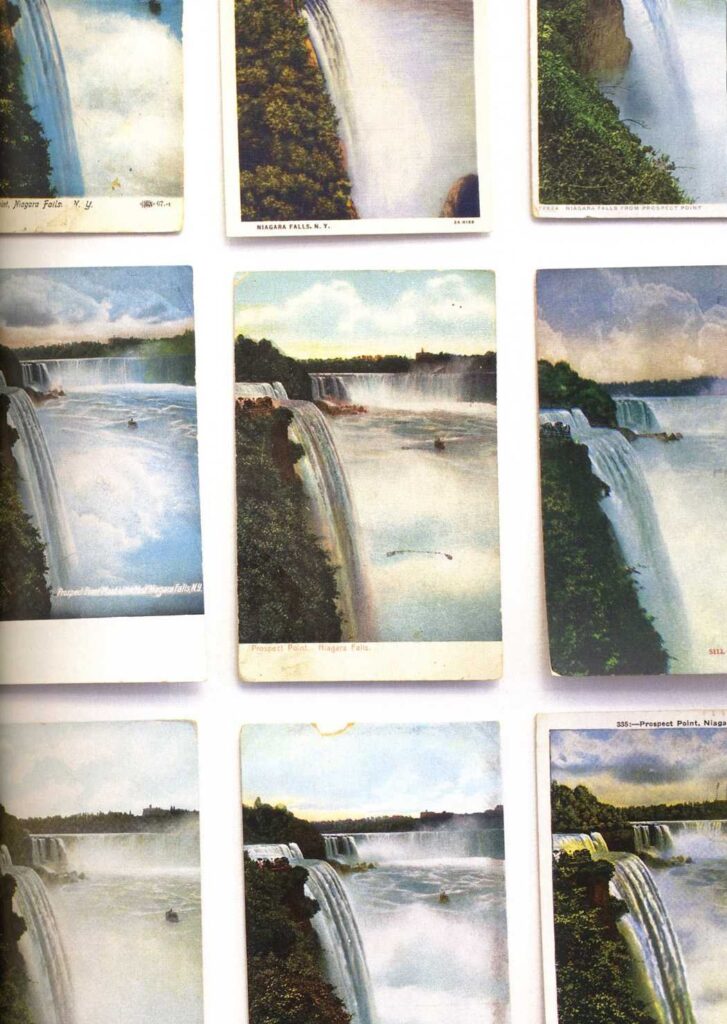

Zoe Leonard

You See I Am Here After All, 2008

The installation includes 3,851 vintage postcards

(Detail)

12’ x 147’

We must understand landscape within the definition of Omniscape—given by Michael Jakob—which states that “landscape is everywhere: in iPhones, PCs, television screens, advertisements, yogurt packaging, trucks… The whole world is covered with landscape images. The density of the representation of landscape seems immense as if it formed a huge crust over the earth.”2 A crust that is necessary for us to understand what surrounds us and be able to capture it visually and sensorially.

The transition from landscape to Omniscape, in all its breadth, is justified in a world covered in landscape images, in which art participates as an interpreter and appropriator of its surroundings in contemporary times. The Omniscape is produced in contemporary art from various creative standpoints, be they aesthetic or interpretative, or an abstract representation of a non-concrete place, or a mental construct, “(…) or as landscapes that are the starting point for the formation of a territorial identity and can lead to social or cultural criticism. They all have in common the use of contemporary language when approaching a territory to turn it into a landscape from an artistic point of view.”3

Cristina Iglesias

Pozo IV, 2011

Resin with bronze powder, motor, water and electronic system

That is where the art of this time, contemporary art, comes into play by understanding the landscape starting from the visible and the invisible in order to allude to emotional states construed through merely human concepts such as loneliness, unrest, or the ambiguous present stillness.

Contemporary art’s Omniscape is a human landscape generated from the subjective apprehension of the environment and in the knowledge of the artistic strategies carried on by a long tradition of world representation, which now spreads out like the crust of a nature created by that which is human.

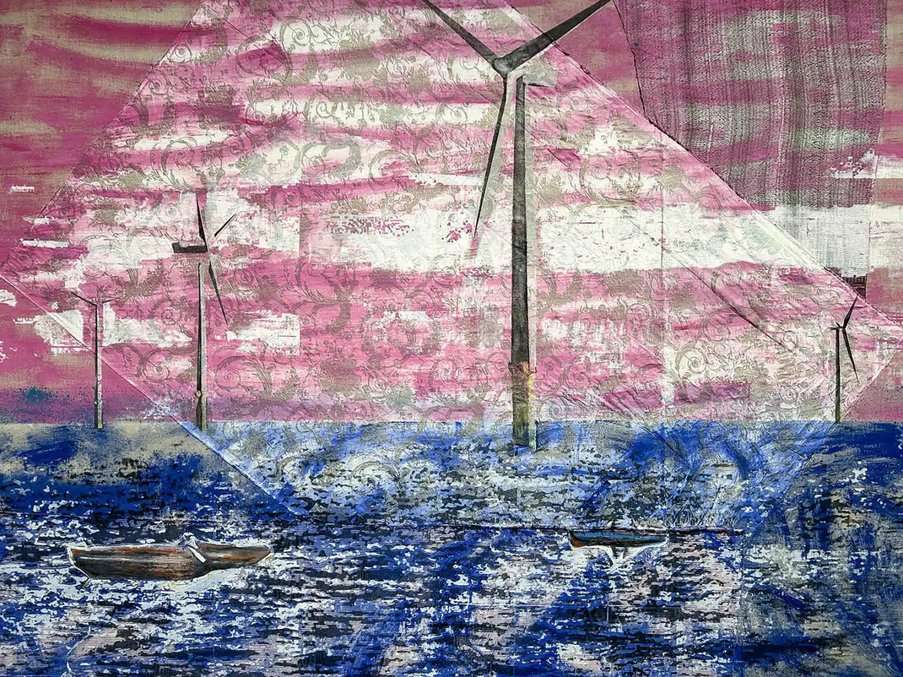

Shezad Dawood

Gwynt and Mor, 2018

Acrylic and vintage textile on canvas

77.95’ x 112.5’

Contemporary art has broadened the idea of that which is human and decides the landscape for one or another, with the intention of avoiding the perceptive absence of created landscapes and what they enclose in their omnipresence, in their being Omniscape, where landscapes that traditionally were not landscapes become visible to artists and the public who watches them.

Shezad Dawood

Gwynt and Mor, 2018

Acrylic and vintage textile on canvas

77.95’ x 112.5’

1 Nogue, Joan. “El paisaje como constructo social”, in: La construcción social del paisaje, Madrid, Ed. Biblioteca Nueva, 2007, pp. 11-12

2 Jakob, Michael: “Metacrítica del omnipaisaje”, in: Teoría y paisaje: reflexiones desde miradas interdisciplinarias. Theory and Landscape: Reflections from Interdisciplinary Perspectives, Théorie et paysage: réflexions provenant de regards interdisciplinaires, Barcelona, Cataluña Landscape Observatory, Pompeu Fabra University, p. 106

3 Yolanda Torrubia Fernández: “La construcción social del paisaje”, in: La construcción social del paisaje, (Cat. Expo.), Andalusian Center for Contemporary Art, 2015, p. 33

Visitors